The systems thinker

8 October, 2025

Introduction

In what is considered the largest global IT outage, a worldwide crash of computers running Windows caused estimated damages of €8.59 billion. A kernel failure triggered by Falcon software, developed by the cybersecurity company CrowdStrike, caused millions of machines to stop functioning, severely impacting IT infrastructure across critical industries. This incident reveals a harsh truth: our infrastructure is fragile, hanging by a thin thread. The uptime of most machines is just one logic flaw away from crashing. Due to the interconnected dependencies between systems, the effects of a single fault can ripple far and wide.

Systems

Systems are all around us, sometimes physical or conceptual, made up from interdependent parts that work together to achieve a purpose. We interact with various systems when we engage in countless seamless interactions during our day. Systems can interconnect through communication of information, and as a byproduct this interconnectedness raises the overall complexity of a domain. Now, systems don’t always work and problems that appear within these domains are complex in nature. People are hardwired to navigate this complexity by thinking, the cognitive process of experiencing or manipulating ideas, images, mental representations, or other elements. In his book, Daniel H. Kim explains systems and levels of thinking, categorizing this cognitive activity into three distinct levels.

Levels of thinking

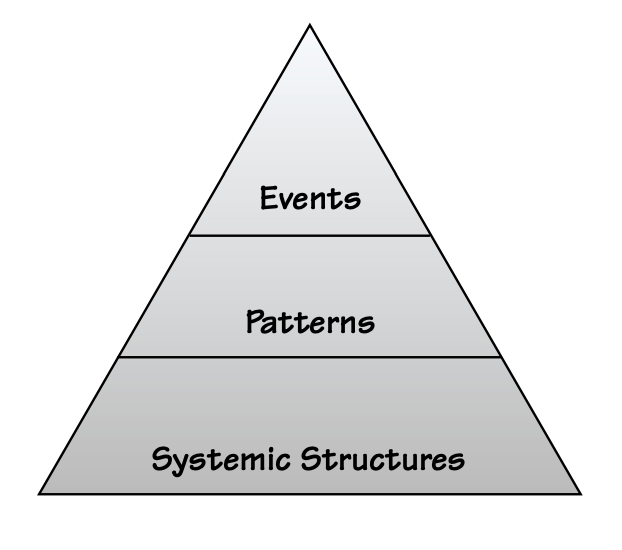

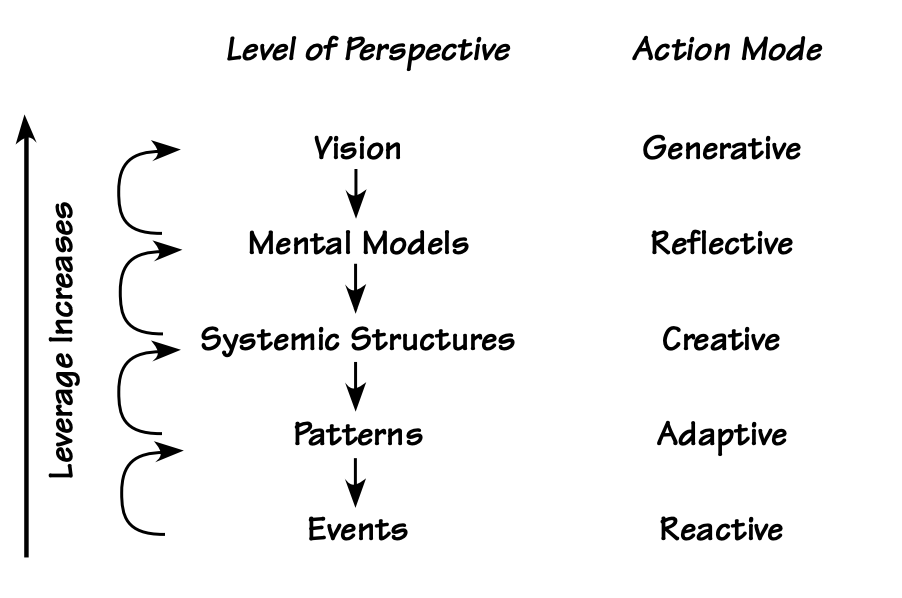

The first layer consists of events, observable occurrences that happen day-to-day. The second layer involves patterns, which are recurring events that can exhibit certain trends. At the bottom, we have systemic structures, where different parts work together to generate patterns and events. He argues that we live in an event-oriented world, but it is fundamentally driven by systemic structures. Generally, most people find comfort at the observable and easier-to-understand event level, while other levels are more abstract and harder to notice. According to him, higher levels amplify leverage, increasing the effectiveness and type of actions we take. This model is extended with two more levels beneath systemic structures: the mental models layer, which describes our beliefs and assumptions on which a systemic structure is built, and the highest level, a vision, which is a depiction of the future and a destination that guides the direction of mental models.

Visualization method

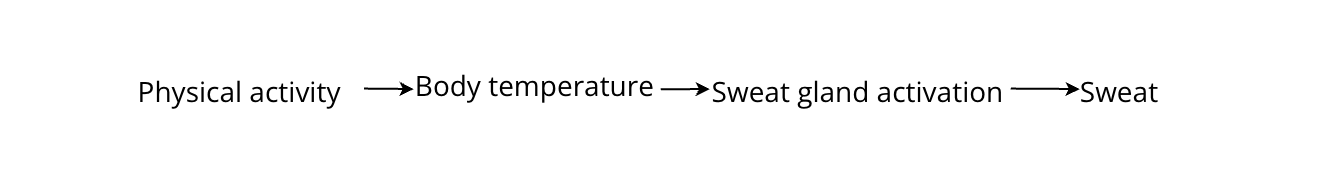

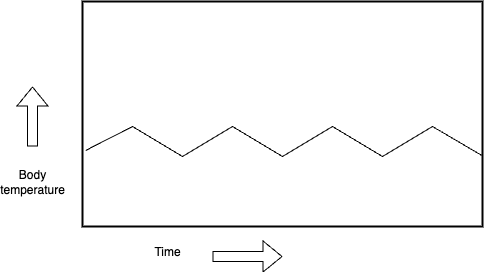

Now, suppose we observe a pattern of events in the world that we know emerges from an underlying system. What tools do we have to grasp such an intuition? To visualize and formulate occurrences, we naturally default to an event-based view, where a series of linear cause-and-effect events describe the situation. For example, we start to sweat when we engage in physical activity, knowing from our childhood biology classes that sweat functions to decrease our core body temperature. We attempt to create a linear view. Let’s depict this system using the following simple diagram:

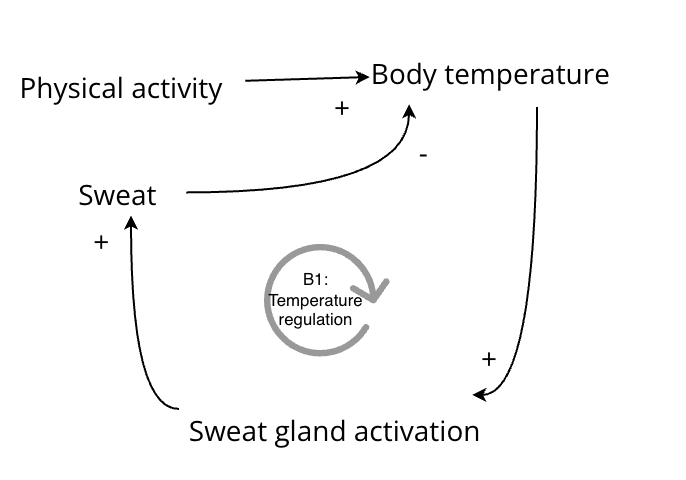

While this view allows us to understand what and when something happened, it cannot provide insight into the why and how. To understand systemic structures dynamically, we should look at them as ‘loops.’ Thinking in loops allows us to see how a system changes behavior through feedback steps in the process.

Feedback loops

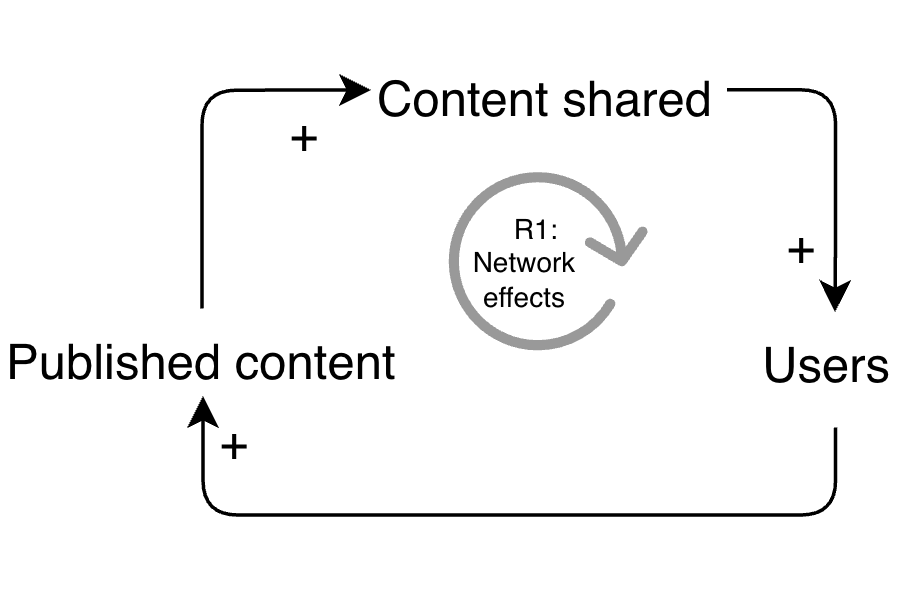

Let’s extend the idea of systems by distinguishing between reinforcing and balancing processes. A reinforcing process is driven by positive feedback in a system, where a change in one direction leads to more change in that direction. In contrary, a balancing process aims to correctively maintain a level or value, for instance, if you engage in physical activity, your body temperature will rise. If your body temperature rises, your sweat glands are activated, causing you to sweat, which reduces your body temperature. The depiction of such dynamics require a more fitting Causal Loop Diagram (CLD).

The image depicts an oversimplified body temperature regulation system. The arrows indicate the direction of this process, while the plus and minus icons represent positive or negative effects on the subsequent node in the system. Now, how does body temperature change over time? A way to depict this is with behaviour-over-time graphs. A graph like this allows us to see how variables in a loop change over time. In this case, we observe that as core body temperature rises above 36 degrees, the system corrects itself by sweating, thus negatively affecting the temperature and bringing it back to the correct level.

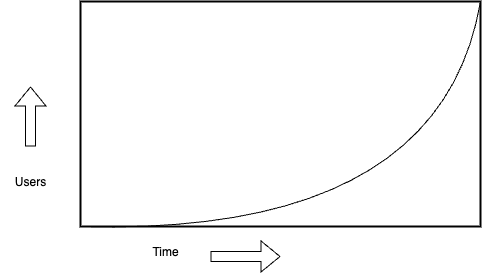

Another type of loop is the reinforcing loop, where positive change compounds exponentially until a balancing loop intervenes. If unchecked, this loop can drive exponential growth or decline, as it does not discriminate. A well-known example is the network effect in social media platforms, which drives exponential growth. As more people join the platform, the amount of content increases, making it more valuable and attracting a larger audience.

The nature of this system is that it is self-reinforcing and compounds exponentially. It is only when a balancing loop stops the process and stabilizes the system, think for example about the limitation on the number of potential users who can download a social media app. However, until that happens, a behavior-over-time graph will display the following pattern.

Final thoughts

This is a very short dive in the world of system thinking, a skill that is considered critical, high-level and in demand. It is fair to say that any professional will find benefit in it, due to its general applicability. For software engineer, the rise of automated code generation has made it even more important, so long as AI does not have complete understanding of the context surrounding a problem, it will struggle to make an accurate analysis. Cheers.