Constructing a compiler

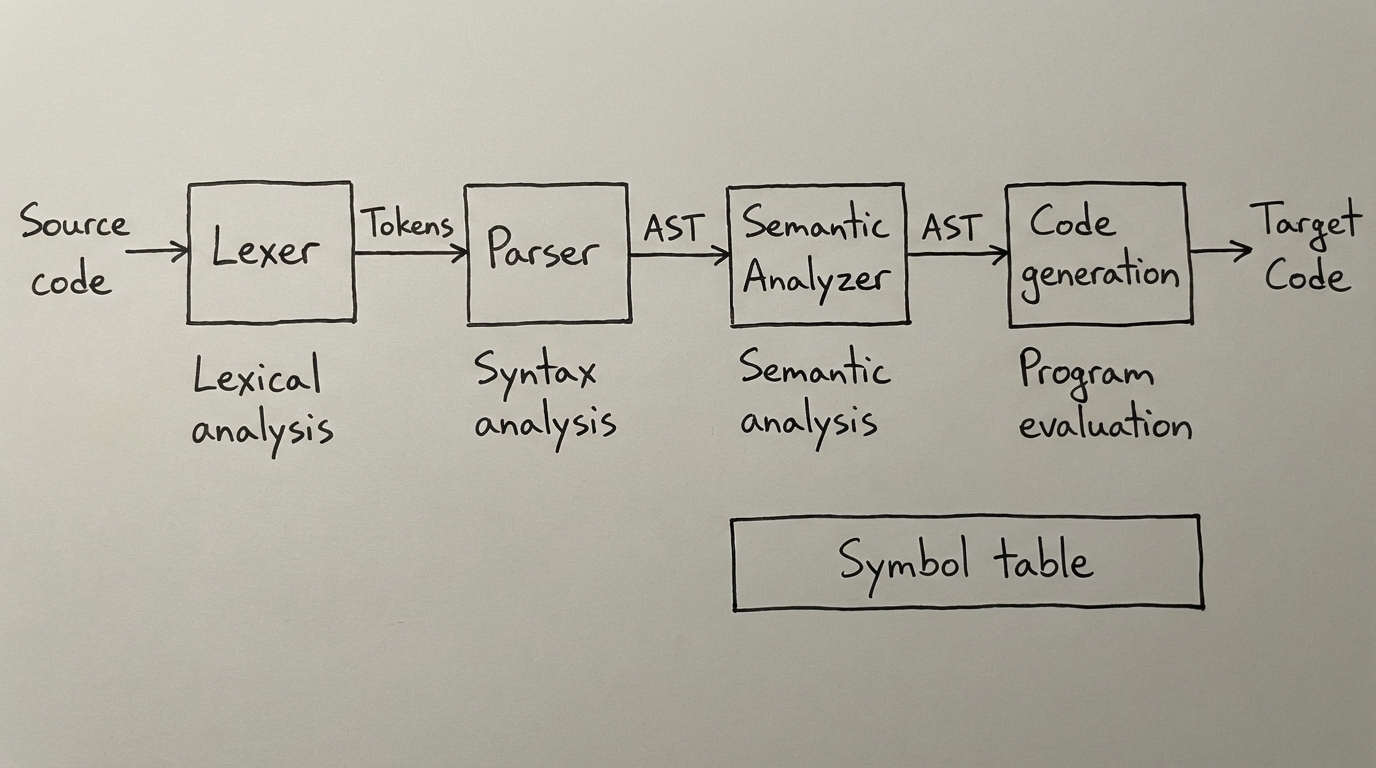

If you want to completely change the way you look at program code, then I recommend constructing a compiler. These programs are used to translate high-level human readable programming languages into machine-executable code, typically instructions in assembly. The compiler comes in many flavours, but for this project we implement a multi-pass compiler, for a C-like language designed by the University of Amsterdam.

1. From code to tokens

Compiling source code starts by translating the character stream into meaningful units called tokens. Essentially, we define tokenization rules in a lexical analyzer. These rules determine what keywords and symbols are valid in our programming language. For some language elements we use regular expressions, for example for one and multi-line comments. The code snippet below shows a few of these rules defined for the Flex lexical analyzer.

"/*"((("*"[^/])?)|[^*])*"*/" { /* A COMMENT, DO NOTHING WITH IT */ }"//".* { /* A COMMENT, DO NOTHING WITH IT */ }

"if" { FILTER( IF); }"else" { FILTER( ELSE); }"while" { FILTER( WHILE); }"do" { FILTER( DO); }"for" { FILTER( FOR); }Everytime a sequence of characters in the code stream matches a rule, a token is produced, eventually we are left with a sequence of tokens that represent our code. In our example above we deal with comments, and the language we are compiling from, like many other languages, do not handle any commented text, so we do not produce any tokens for it, but we do for any other construct such as function definitions, producing the example below.

# Function definition from the source codeint main() {}

# Token output produced by the lexical analyzerINTTYPEID(main)ROUNDBRACKET_LROUNDBRACKET_RCURLYBRACKET_LCURLYBRACKET_RFinally, we debugged the lexer and were sufficiently confident in the lexers ability to produce a correct sequence of tokens, the lexer was integrated into the compiler, forming the foundation for our compiler.

2. Makes this no still sense… uh.

At this point, the token sequence generated by our lexer is not necessarily correct, that is to say that we did not define ‘correct’ yet. By creating a grammar, we are able to define the syntactic structure of the language. We begin by defining the constants and expressions as specified in the language. We define statements, parameters and arguments by creating three types of grammars for each: singular, one or many, and optional many grammars, but could also be handy for function definitions that do not have any parameters.

block: CURLYBRACKET_L stmts_opt CURLYBRACKET_R { $$ = $2; } | stmt { $$ = ASTstmts($1, NULL); };Some grammars, like those of function definitions and variable declarations, do not not fit in one rule, it can grow too large and unmanageable, and increases the change on ambiguities that result in so called shift/reduce conflicts, these can be splitted. Finally, if parsed correctly with a tool like Yacc, an Abstract Syntaxt Tree (AST) is produced, to be used as an intermediate representation during succeeding compilation steps.

3. Determining the semantics

The semantic analysis uses the Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) and a Symbol Table to perform tasks like type checking, scope resolution, and variable declaration checks. We traverse the AST with a helper method, enabling inspection and manipulation of the intermediate representation.

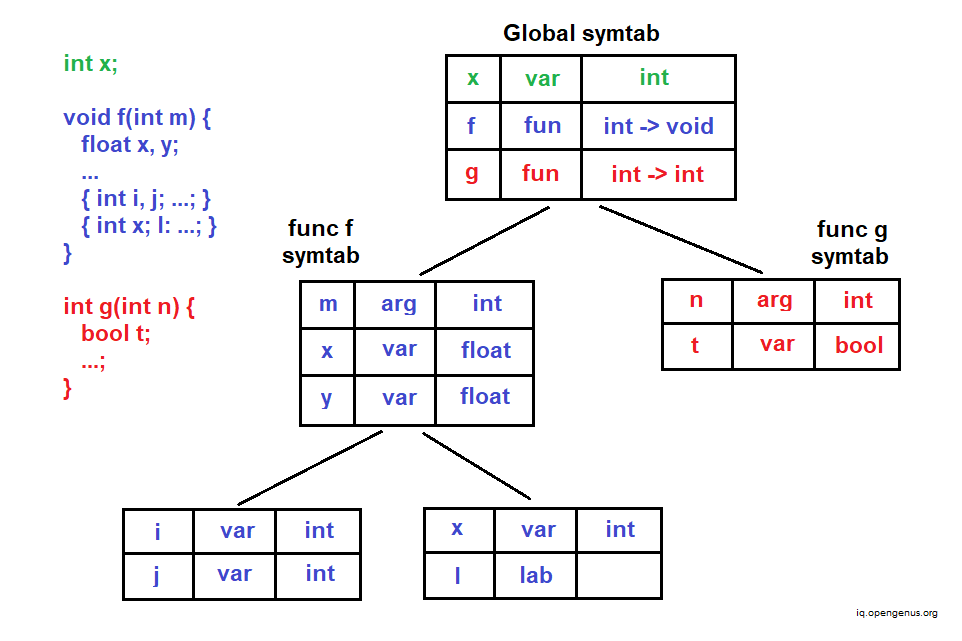

During the traversals we need some way to keep track of identifiers. For this, a symbol table is devised, and implemented with a symbol table node, used to construct a linked list, attaching it to the global program and function definition nodes. The node consists of a initial head (child) symbol table entry node and an outer symbol table entry (child) node that references the parent symbol table node. We end up with a structure like the one shown below.

We create helpers to create a new symbol table entry, and append it to the end of the symbol table head node, and link the entry to the declaration being visited. If an entry was already defined, it raises an error message. For the software engineers among us, this error message might look something like the one’s you had in your earlier engineering days, when the countless SyntaxError: Identifier 'x' has already been declared errors triggered you to learn difference between variable assignment and initialization.

To prepare for code analysis and generation, we focus on normalizing program structures, starting with induction removal to standardize loop shapes and a variable initialization pass that separates assignments and relocates global setups to a generated _init function. This required refining the symbol table lookup logic to prioritize local scope validation before falling back to outer layers, to make sur that variables resolve to their correct declarations. With the structure defined, we can implement name binding as a semantic analysis step to link AST nodes, particularly function calls via arity-based signatures, to their definitions, paving the way for the type checker. This final phase uses bottom-up inference, propagating types from constants through expressions and statements to detect mismatches, enforce return constraints, and validate operations before code generation, and generate type errors.

4. Communicating with a machine

To prepare for code generation, we first implemented several AST transformations designed to simplify the backend logic. This included standardizing control flow by converting for loops into equivalent while loops and injecting ternary conditions to handle negative step values.

node_st *condition = ASTternary( ASTbinop(CCNcopy(step), ASTnum(0), BO_gt),

ASTbinop(ASTvar(NULL, STRcpy(FOR_VAR(node))), CCNcopy(FOR_STOP(node)), BO_lt),

ASTbinop(ASTvar(NULL, STRcpy(FOR_VAR(node))), CCNcopy(FOR_STOP(node)), BO_gt));We also rewrite boolean operations into ternary structures to natively preserve short-circuit evaluation. With the AST normalized, I reverse-engineered the reference compiler’s output to understand these structures and implemented a tracking system that assigns an assembly_index to every Symbol Table Entry (STE). This allows variable nodes to resolve their correct table location during the final traversal, where fprintf instructions generate the bytecode. I verified the result by comparing my output against the reference compiler and running custom test suites covering edge cases like casting, nested loops, and complex branching.

5. Final thoughts

Compilers are incredibly complex systems. A single article can never fully do justice to underlying concepts like Context Free Grammars (CFGs) and Non-deterministic Finite Automatons (NFAs). However, these programs continue to power the world with enormous leverage. Why? Small optimizations can lead to massive gains when projected forward; these gains span multiple metrics, including speed, energy efficiency, and reliability.

Ultimately, building a compiler plants a seed of curiosity. It changes your perspective from simply writing code to understanding how that code interacts with the machine, revealing the opportunities where software engineering truly intersects with hardware constraints.